In partial preparation for an initial analysis of the 2020 Presidential election, some of the first state-level data I gathered related to the Electoral College. That data subset quickly took me down a rabbit hole chasing after a rodent that’s been on my nerves for a very long time.

This is why I have a blog. I need to vent.

First, a short civics lesson is required. [Yes, Dr. Philpott, I was apparently paying attention in your American Experience class during my Freshman year at UT. Who knew? Sure, I did my own research years later but I can trace at least some of my political interests and my tendency to question everything back to your class. Thank you.]

First, let’s recognize that the Founding Fathers did a phenomenal job defining a very complex governmental structure that has survived for over two centuries. However, they were human and had to make compromises to complete a Constitution that could actually be ratified by the states. In many cases, those compromises were brilliant. However, with respect to the election of the President, not so much.

The process to elect the President is codified in Article II, Section 1 of the U.S. Constitution as modified by the 12th and 23rd Amendments. In essence, the Constitution mandates that each state select a number of Electors equal to the total number of U.S. Senators and U.S. Representatives from that state. These Electors then each cast separate votes for the President and Vice President.

If one or both elections fail to get a majority of Electors, then all hell breaks loose. With processes that would confuse Rube Goldberg, the House and Senate then decide the outcome(s). This topic might deserve its own post at some point, particularly since an Electoral College tie is a distinct possibility these days. For now, however, we’ll just consider the basic Constitutional mandates above. They are quite literally as simple as the preceding paragraph.

Note that:

- The Constitution does not mandate how a state’s Electors should be selected.

- The Constitution does not mandate how a state’s Electors should be apportioned between candidates.

- The Constitution does not mandate how a state’s Electors should vote.

These important decisions are left entirely to each state. Thus, a whole lot of what we accept as givens with respect to the Electoral College are just state laws and practices, not Constitutional mandates. Indeed, even the term “Electoral College” isn’t in the Constitution.

So, before we get to the states’ implementation issues, we need to understand why we have Electors in the first place. There were two primary reasons:

- The Founding Fathers simply didn’t trust the masses.

- Alexander Hamilton summarized his rationale in The Federalist Papers: No. 68. Therein, Hamilton claimed that Electors would be “men most capable of analyzing the qualities adapted to the station” and that they would be “most likely to possess the information and discernment requisite to such complicated investigations.” In his view, Electors would prevent a candidate with “Talents for low intrigue, and the little arts of popularity” from conning his way into the Presidency and prevent “the desire in foreign powers to gain an improper ascendant in our councils.” Hamilton not only thought that it was acceptable for each state Elector to vote independently of any apparent state preference. He considered it their purpose to vote in possible defiance of uneducated popular opinion that favored an unqualified candidate with foreign influences.

- That’s almost funny. Almost.

- The Electoral College was an accommodation to slave-owning states.

- The number of Electors is tied to representation in Congress, representation in Congress is based on population, and the Three-Fifths Compromise originally counted five slaves as equal to three free people for population purposes. While James Madison originally favored the direct election of the President, he wrote in his Notes of the Constitutional Convention that it would put southern states like his at a disadvantage. Under a direct vote approach to Presidential elections, states would get no political benefit from their citizens’ ownership of non-voting slaves. Hence, Madison lobbied for the Electoral College.

- That’s not funny at all.

The states, in their collective wisdom over time, subsequently took this framework of a bad idea and managed to make it worse.

All states currently hold popular elections for President and most states (48 states and DC) then assign all of their Electoral votes to supporters of the candidate receiving a plurality of the popular vote. Only two states (Maine and Nebraska) apportion their Electors. For what it’s worth, Hamilton favored choosing Electors by district but eventually decided to leave that decision to the states. Unfortunately, once one state tried to increase its influence with a winner-take-all scheme, most of the other states quickly followed suit so as to not be disadvantaged.

Since all states have decided that their Electors should be party-assigned, hard-line loyalists, Electors are very unlikely to vote otherwise. So-called “faithless Electors” have appeared but last impacted an end result in 1796. Thus, large numbers of voters in each state – from both parties – are completely without representation in the Electoral College.

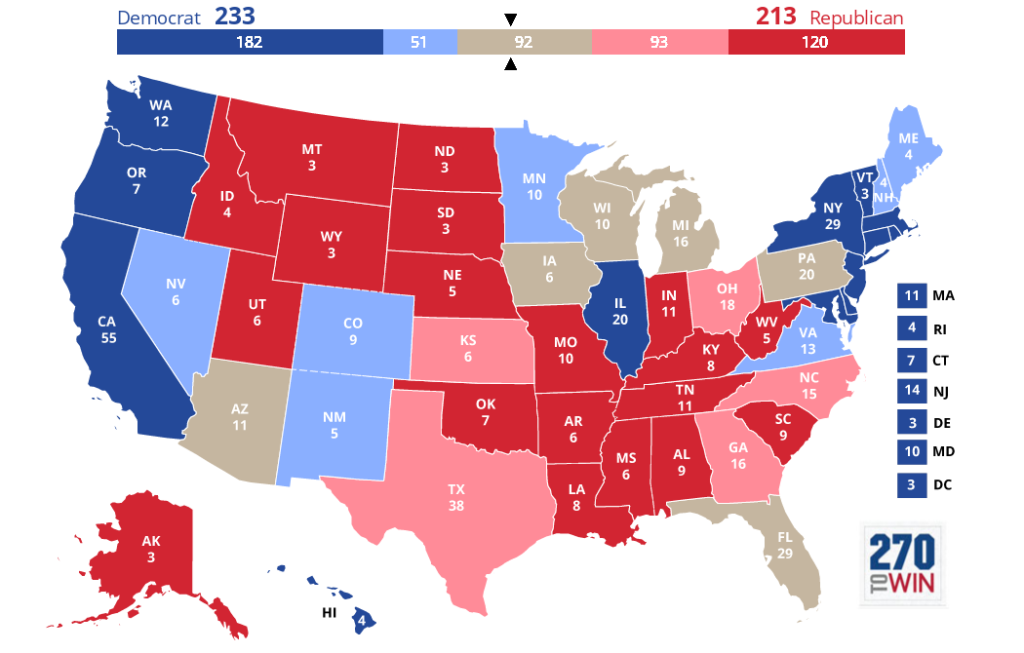

We are all well aware of the recent history of Electoral College results being at odds with the popular vote. Al Gore beat George W. Bush by 543,895 popular votes but lost the Electoral College 266 to 271; Hillary Clinton beat Donald Trump by 2,868,686 popular votes but lost the Electoral College 227 to 304.

What most people fail to realize is that it is largely an accident that Electoral College results and popular votes have ever been close at all.

In the current political environment, both Democrats and Republicans generally enjoy a mix of both large and small states. Imagine, however, a scenario where the smaller states all favored Party A and the larger states all favored Party B. Using Elector counts by state, the 40 smallest states plus DC account for 282 Electors – more than enough to decide the Presidency. Using total vote counts by state from 2016, those same 40 states plus DC accounted for 66,253K votes. Since only a popular majority is required to capture all of a state’s associated Electors, we can cut that vote total in half, making the required vote count 33,168K. Since a total of 137,536K votes were cast nationwide in 2016, that means that 24% of all voters could have easily won the election.

Think about that. The President of the United States could have been legally elected in 2016 with less than a quarter of the popular vote and with no votes in the 10 largest states having any consequence at all.

It would be tough to consider this scenario fair by any standard. If you’re thinking it could never happen, remember that California cast its Electoral votes for George H.W. Bush and that Texas cast its Electoral votes for Jimmy Carter. Things change. Things change quickly. Things change in unpredictable ways.

The Connecticut Compromise created our bicameral legislature with states having proportional representation in the lower chamber and equal representation in the upper chamber. This was the key to avoiding what Alexis de Tocqueville would later refer to as “the tyranny of the majority” in the Legislative branch of our government. What the Electoral College essentially enables in the Executive branch is the tyranny of the minority, whereby a minority collection of voters can enjoy an unchecked ability to override the will of the majority in selecting the President.

A revamping of the way we select our President could also correct an unfortunate side-effect where Presidential candidates campaign almost exclusively in a handful of “swing states” largely ignoring the vast majority of “safe states” that heavily favor either party. A national election in 1787 might well have been impractical. The Founding Fathers can hardly be faulted for not predicting radio, television, and the Internet. However, there is simply no modern excuse for not correcting this affront to the basic tenets of democracy. It’s safe to say that most of the framers of the Constitution would be appalled by what the Electoral College has become.

There are three possible solutions:

- Adopt a Constitutional amendment that substitutes a nationwide popular vote for the Electoral college. While this is the cleanest approach, it’s a tough hurdle since it requires approval by two-thirds of the Senate, two-thirds of the House, and two-thirds of the States.

- Adopt a proportional allocation of Electors in every state as Hamilton intended. This isn’t a perfect solution and the winner of the nationwide popular vote might still not get a majority of Electors. However, it would definitely be better. Unfortunately, there is little reason to believe that all states could ever act in tandem to implement this change.

- Adopt a multi-state agreement where the winner of the national popular vote gets awarded all of the Electors in each state participating in the agreement. The advantage of this solution is that it only requires the buy-in of enough states to form an Electoral majority. There is, in fact, an effort underway to implement this plan. The National Popular Vote bill has been enacted by 12 states with a total of 172 Electoral votes. It could be put into practice if it gets support from additional states with a total of 98 Electoral votes.

Do I think any of the above are actually going to happen? Unfortunately, no. Something needs to change, but it probably won’t in my lifetime. We’re likely stuck with what we have and the best we can do is figure out how to game the existing system to our advantage while the other side tries to do the same.

You can almost smell the democracy in action. The Founding Fathers would be so proud.